There are a great many phrases you can use to describe greater Miami, but “racially harmonious” would not be one of them. From the days of employment identification cards required for people of color to get into Miami Beach, to near-riots over a civic language ordinance, there has always been racial tension in Dade County. And while racial and cultural issues still remain a major concern in 21st-century South Florida, never were our problems more evident—or more explosive—than in the late spring of 1980.

The Miami race riots (also known as the Arthur McDuffie Riots) of May 1980 were the first major race riots after the end of the civil rights movement. The Miami Black community, long abused and neglected by civic leaders who, among other things, placed I-95 straight through the cultural center of their neighborhoods, was getting angrier by the day. Recently arrived Latin and Haitian immigrants were taking jobs and social benefits that had traditionally belonged to Blacks. Cuban refugees wielding money and power were beginning to take control of the city, and as such were awarding minority contracts and jobs to Cubans instead of African-Americans. This, combined with the continuous poverty and degradation of their neighborhoods, had Miami’s Black community ready to snap.

And so it was in this volatile environment that former Marine Arthur McDuffie rode his Kawasaki motorcycle at over 100 mph on the morning of December 17, 1979. Several Miami police spotted McDuffie and attempted to pull him over. Because he had a suspended license and had already received one ticket for it, the Black insurance salesman fled. After a few minutes of leading the police on a high-speed chase, McDuffie finally pulled over, throwing his hands in the air and saying “I give up.”

The police, possibly stressed from the ever-increasing crime in the area or maybe just hell-bent on making someone pay, did not accept McDuffie’s surrender. According to witnesses (most of them police), he was surrounded by a dozen Miami police officers and beaten. And beaten and beaten some more. Some held him down while others struck him with batons and flashlights. His skull was cracked clean in half and after 8 minutes of severe violence he was taken to a nearby hospital where he slipped into a coma and died 4 days later. The officers claimed that McDuffie had sustained his injuries as he fell off his bike. The Dade County Coroner saw things a little differently.

According to the coroner, there was no way the multiple blunt-force wounds McDuffie received would have been possible from a mere bike accident. The police department began an investigation of the officers involved and found a very different story than the one mentioned in the officers’ reports. After the internal inquiry was over, it became apparent that what happened to McDuffie was no accident. He had been handcuffed, pulled off his bike, and beaten severely. In an attempt to cover up their wrongdoings, the police went to great lengths to make the scene look like an accident. They drove over McDuffie’s bike with a squad car to make it look accident-damaged. They gouged the road with a tire iron to look like bike tracks and threw the victim’s watch down a gutter. But these small acts could not cover up what they had done.

As the investigation continued, the brutality of the beating became more evident. Witnesses described the officers as fighting to take turns for a shot at McDuffie. Another described them as “a pack of wild dogs attacking a piece of meat.” The assault continued for nearly 20 minutes, with McDuffie being smashed across the head with a flashlight, cracking his skull “like an egg,” as the prosecution later put it. Originally, six officers were to be indicted for McDuffie’s death: Officer Alex Marrero for 2nd degree murder, Sgt. Ira Diggs and Officer Michael Watts for manslaughter and aggravated battery, and Officer Ubaldo Del Toro and Sgt. Herbert Evans, Jr. for accessory after the fact. Officer William Hanlon was also to be charged, but his testimony was thrown out by Judge Lenore Nesbitt. All except for Marrero, a Cuban, were white.

Hanlon had been accused of holding McDuffie down while others beat him, and for assisting with the cover-up. But during his polygraph examination, he had apparently not been informed of his right to remain silent or his right to an attorney. His account of the incident, which had led to much of the prosecution’s case, was immediately thrown out. This was especially important in the case against Officer Marrero, whom Hanlon had claimed to have delivered a two-handed flashlight blow to McDuffie’s head. Marrero found allies in Miami’s Cuban-American community, claiming that he was being scapegoated because he was the only minority involved in the incident. This, of course, was back when a Cuban-American could claim minority status in Dade County.

The city, and especially its Black community, became outraged. Citizens marched in front of the Dade County justice building carrying a black coffin. The NAACP sent letters to the federal justice department asking them to monitor the trial. Miami’s Black residents had long complained about police brutality, but as it does in most places their voice fell on deaf ears. But the McDuffie case was different. This was no drug-peddling street thug or common ghetto criminal; this was a man who had served his country as a military police officer, worked in the white-collar world and was senselessly killed by a group of deranged police. Police who, combined, had 47 citizen complaints and 13 internal review probes in the past seven years. The combination of a sympathetic victim and extremely unsympathetic attackers made this situation especially dangerous.

The situation was considered so dangerous, in fact, that Judge Nesbitt granted the defendants’ request for a change of venue to Tampa. She called the case “a time bomb I don’t want to go off in my courtroom or this community.” What the judge failed to realize, however, was that no matter where the fuse was lit, it would eventually burn all the way back to Miami.

The trial began March 31, 1980 in Hillsborough County and was led by prosecutor Janet Reno. In a glimpse of Reno’s future stellar judgment, the 6-member jury was made up of all white males. Three officers, Hanlon, Charles Veverka and Mark Meier testified that police had surrounded McDuffie, pulled off his helmet, beaten him with flashlights and nightsticks until he was motionless, and then attempted to cover it up. Dr. Ronald Wright, a Dade County medical examiner, testified that McDuffie had received the worst brain damage he had ever seen. This, apparently, was not enough for the jury.

While Del Toro had been acquitted May 8, with Judge Nesbitt agreeing that the state had failed to prove its case against him, the other five officers were acquitted May 17 after a lengthy three hours of deliberation. Why exactly the jury found them not guilty will never be known, but it didn’t matter much to the Black citizens of Miami.

As soon as word reached South Florida that the McDuffie cops had been acquitted, residents began a march from Liberty City (Miami’s largest Black neighborhood) to the Dade County justice building. Upon arrival the NAACP could not produce a speaker, and someone went to the front of the crowd and asked for a prayer. One member of the crowd yelled “We’re tired of praying! Let’s march in the streets!” The crowd soon grew unruly and out of control. Bricks began to fly, police cars began being overturned and burned. The city was about to fall into chaos.

Back in Liberty City, things weren’t much better. Jeffrey Kulp, a 22-year-old white motorist who ended up in a Black part of town, was being attacked by the angry mob right in front of the Liberty Square housing project. His brother had been driving a car with Kulp and a female friend, when he lost control and ran into a 7-year-old Black girl. This was perhaps the worst possible thing a white person could do in Liberty City at that particular moment. Kulp was pulled from his car, beaten, stabbed, shot and run over before he became the first casualty of the McDuffie riots.

When

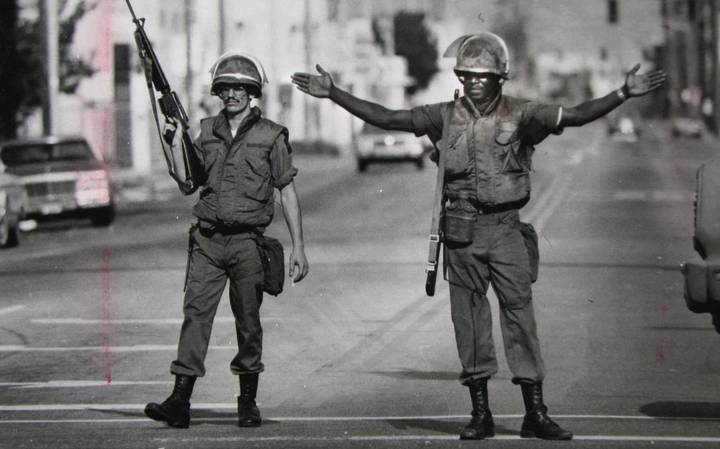

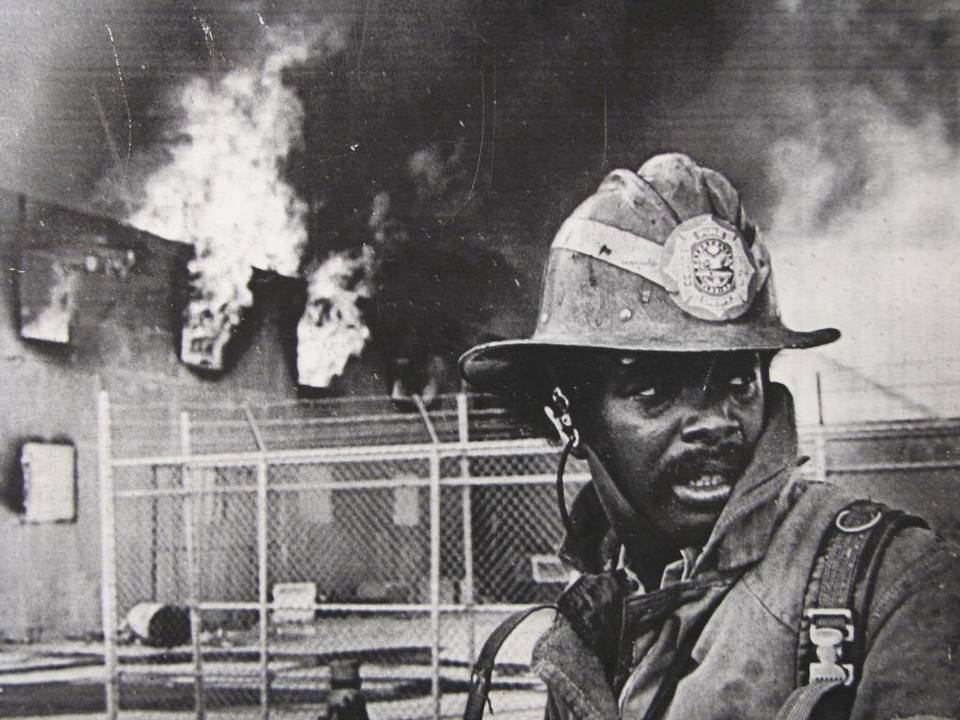

The violence escalated as two more deaths ensued and rioting, looting and burning became the norm in the city. The violence spread to other Black sections of Miami such as Overtown and Coconut Grove. Then-Governor Bob Graham sent 500 National Guard troops to Miami, but it did little to quell the violence. Rioters continued attacks on white-owned businesses, white motorists who happened to stumble through the wrong areas, and even the Dade County Department of Public Safety. A city-wide curfew from 8PM to 6AM was issued as well as a temporary ban on the sale of firearms and alcohol. Graham sent an additional 2500 guardsmen and the violence finally subsided.

When all was said and done 18 people had been killed (8 white and 10 Black) and $100 million in property damage had been done. And, as is most often the case, the rioters did the majority of their damage to their own neighborhood. Longstanding businesses were gone, houses and apartments were destroyed, and an area that was already in bad shape had been reduced to ruin. While the Federal Government did allocate funds for rebuilding, and the state and city made some efforts, Liberty City still remains one of the poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods in America.

The McDuffie family, including his mother, 3 children and ex-wife he was planning to re-marry, eventually received a $1.1 million settlement from the Dade County Commission. The police were re-hired after their acquittal after a threatened walkout by the Fraternal Order of Police. After intense pressure from the NAACP, the McDuffie police were tried for civil rights violations in federal court, but again produced no convictions. A few days after the acquittal, Michael Watts attempted suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning, but survived. And Bill Hanlon, who turned in his badge voluntarily after the incident, worked for 20 years in a civilian job with the Metro police department. He then went to law school and is attempting admission to the Florida Bar despite his checkered past. He now does extensive community work with the poor and minorities around South Florida.

While the individual parties involved in the McDuffie riots have moved on, some would debate whether or not the city has. The 1980s changed Miami greatly. The Mariel boatlift had just ended when the riots began and the racial makeup of Dade is not what it was in 1980. Much of the middle class has left, there are few whites remaining, and the Black community still struggles to have its voice heard. So while many of us living here feel that something like this couldn’t happen again, you need only to look around you to realize that it can. Racial tension will always be a part of daily life in Miami. We just have to do our best to keep it under control.

Editor’s Note: Originally published in August 2007 and updated in 2026 for clarity while preserving Matt Meltzer’s storytelling and investigative detail.

Comment disclaimer:

Some comments below originated on a previous version of MiamiBeach411.com. As a result of platform migrations, displayed comment dates may reflect import timestamps rather than original posting dates. Many comments date back to the early 2000s and capture community conversations from that time. If you have local insight, updates, or memories to share, we welcome your comments below.

This story has been part of Miami Beach conversations for decades—and it’s still unfolding. Add your voice.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Join the conversation